|

|

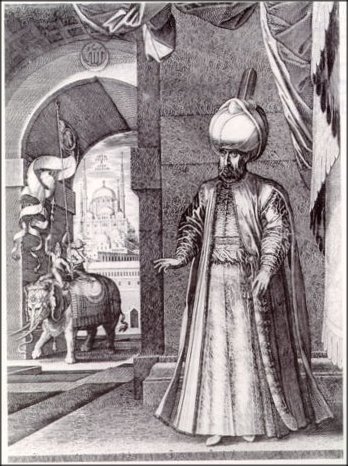

Like any new Sultan eager to consolidate his power, Süleyman had to prove himself in the field of ghaza: Selim’s conquests had doubled the size of the empire and caused despair in Europe, but he had died before he had won the great victory in the West which he had planned for, for example, in the building of a great shipyard in Istanbul (begun 1515). Success depended on possession of the two fortresses of Christendom: Rhodes (gate to the Mediterranean) and Belgrade (gate to central Europe). In 1519, Charles V had ascended the Habsburg throne, and in 1521 war broke out between him and Francis I of France, the other great Christian ruler, dividing Europe into two camps. It would now be impractical to launch a combined Crusade against the Ottomans, and these were the perfect circumstances for an Ottoman offensive against Europe. Such were the conditions at the beginning of Süleyman’s reign.

| A.11.a. | Habsburg Wars and the Battle of Mohacs (1526): | |

He captured Belgrade in August 1521 and Rhodes in December 1522. Francis I was taken prisoner by Charles in 1525 and asked help from the Ottomans; in 1526 a French ambassador asked Süleyman to launch both land and sea offensives to stop Charles becoming supreme in Europe. Venice also sided with the Ottomans in 1525. However, Ottoman interests required an attack on Hungary and they won a resounding victory at Mohacs on 28 August 1526. An Ottoman puppet, Zápolyai, was made king of Hungary, but pro-Habsburg Hungarians simultaneously elected Charles V’s brother, Archduke Ferdinand, to the throne; he drove Zápolyai out of Buda in September 1527, then asked Süleyman to recognise him as king of Hungary, even offering to pay annual tribute. This offer was rejected since Süleyman considered Hungary as his to bestow, and again promised the throne to Zápolyai.

In 1528 Francis I made war on Charles V; he soon found himself in difficulties and again appealed to the Ottomans, who re-entered Hungary in 1529, gave Zápolyai the Hungarian crown, advanced West against Archduke Ferdinand and laid siege to Vienna for the first time, then withdrew after 3 weeks leaving a garrison of Janissaries in Buda. In the meantime, Francis had signed a treaty with Charles which angered Süleyman though he saw the value of co-operation with France: Istanbul was now one of the most important centres of European politics, and Francis even admitted to the Venetian ambassador in 1532 that the Ottoman empire was the only force guaranteeing the continued existence of the rest of Europe against Charles V. From this point onwards, alliance with France became part of the Ottomans’ Western policy.

In 1531 Francis began to encourage Süleyman to invade Southern Italy in the hope that France could extend its influence over Genoa and Milan, but Archduke Ferdinand attacked Buda again. Süleyman left his admiral Barbarossa to assist the French in the Mediterranean while he himself marched on Austria; this led to another siege of Vienna, but Charles V didn’t appear so Süleyman turned back. The Turkish fleet was defeated in the Mediterranean, and in 1533 Süleyman signed a truce with Ferdinand. Barbarossa was given command of all Ottoman naval forces and made governor-general of Algiers in order to help France continue its war in the Mediterranean; Süleyman even sent Francis 100,000 gold pieces for him to form a coalition with England and German Protestants princes against Charles.

| A.11.b. | The Ottomans & the Reformation: | |

In fact, Ottoman pressure on the Habsburgs between 1521 and 1555 was an important factor in the consolidation of the forces of the Reformation, the European religious and political movement to reform the Roman Catholic Church which was set off by the German priest, Martin Luther, in 1517; Luther actually described the Ottomans as a plague sent by God to awaken the Christians, and an enemy of Lutheranism compared it to Islam. In the C16th and C17th, Ottoman support and encouragement for Protestants and Calvinists were (like the French alliance) one of the fundamental principles of Ottoman policy, with the object of keeping Europe divided, weakening the Habsburgs and preventing the launch of a united Crusade against them. Calvinism was allowed to develop freely in Hungary and Transylvania, and Süleyman offered military help to Lutheran princes in the Low Countries; he also opened the markets of the Levant to Dutch Calvinists, thereby contributing in large part to their mercantile development.

Queen Elizabeth I of England became the champion of European resistance against the Catholic Philip II of Spain, and made friendly overtures to the Ottomans, seeing in them (as Francis I had) the only military power capable of keeping the balance of power in Europe. Süleyman granted trading rights to the English in 1580, after which the English took the place formerly occupied by the French in Istanbul, and in the first half of the C17th, England considered its Levant trade as important as its trade with India.

| A.11.c. | More Trouble with the Safavids (1530s-1555): | |

Süleyman signed a one-year truce with Charles V in 1545, then a 5-year truce in 1547 with Charles and Ferdinand, on Ottoman terms. When Francis I was succeeded by Henry II, Ottoman-French co-operation in the Mediterranean continued, and the Ottomans even occupied Corsica for France in 1553. Peace in the West was essential to allow Süleyman to pursue a campaign against Persia, where the Safavid Shah Tahmasp was continuing the policies of his father Shah Isma’il, provoking the Qizilbash to revolt in Anatolia in 1527. The Shah even gave favourable reception to envoys from Charles V. By 1533, war between the Ottomans and Safavids was inevitable. Süleyman captured and annexed Tabriz in July, and Baghdad in December of 1534, and won control of the Basra-Baghdad-Aleppo silk road, the second important trade route between India and the Middle East. However, as soon as the Ottoman army withdrew, the Persians recaptured Tabriz, and in 1548 Süleyman launched his second Persian expedition, re-taking Tabriz; the war in the East continued intermittently until 1555, with Tabriz and Baghdad under Ottoman rule.

| A.11.d. | Growing Power of the Russians & Ivan the Terrible (1547-1584): | |

|

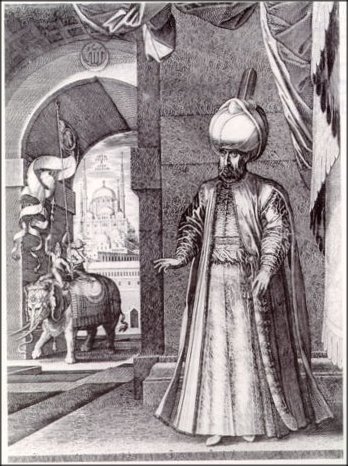

| Ivan 'the Terrible', 1547-1584 |

Conflict with the Persians again brought the Ottomans into

struggle with their allies, the Portuguese, and they now

attempted to drive them out of the Red Sea; on several occasions

Ottoman activity caused crisis on the Portuguese spice market.

This was also a time when the grand duchy of Muscovy was becoming

a threat to the Ottoman dominions, when a struggle started

between them and the Ottoman territory of the Crimea, over the

remnants of the Eastern European lands which had been conquered

in 1251 by the descendants of Chinghiz Khan (known as the Golden

Horde). In 1538 the Black Sea was an Ottoman lake, but when Ivan

IV (‘the Terrible’) assumed the title of Tsar (1547) he

penetrated south as far as the Caucasus area, and by 1559

Cossacks were raiding the Crimean coast for first time (it was

Russian interest in this area against the interests of the

Ottomans that led to the Crimean War, 1853-56, in which –

interestingly – the Ottomans were joined by their historical

allies, England and France). However, action was not taken

against the Muscovites until 1569, after the death of Süleyman,

under the command of his son, Selim II (‘the

Drunkard’), and his Grand Vizier, the famous Sokollu Mehmed

Pasha.