| D.4. | The "Kashan" Style: | |

The fully-fledged "Kashan" style took off at the very end of the C12th, by which time all the diagnostic motifs, which Ettinghausen and others after him have used to identify this style, were established, and remained without modifications until the start of the C14th. Unlike the "Monumental" style, which owed its beginnings to influence from Egyptian lustre, or the "Miniature" style, which took its inspiration from other media, principally manuscript illumination, the "Kashan" style owed nothing to outside influence. It seems that a few distinguished and skilled master potters created this style and perpetuated it as long as they were practising, giving way to the next generation of potters at about the time of the Mongol invasion. This idea will be discussed fully below, in section E.

Click here to look at some typical motifs of this style.

The "Kashan" style is characterised by the treatment of the background: some transitional pieces between the former two styles and this one play with lightening the solid lustre background by texturing it with tiny swirls and spirals drawn in lustre onto the reserve ground; in the "Kashan" style, the texturing is achieved by scratching the spirals through the lustre, giving a lightened effect overall. The figures are still drawn in reserve but are so completely filled in with different patterns that they can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out from the background. The only feature which is kept entirely plain and white is the graceful moon-face, frequently surrounded by a halo.

|

| [1956.33] |

Click here to study this bowl, dated 608 AH / 1211-1212 AD

Of the 13 known signatures in the whole range of Kashan pottery, 7 come from this period, known as the "Kashan" style. Of these 7, only one name occurs more than once, and that is Abu Zaid. As will be discussed in section E, this potter is emerging as a prominent artist in his field, transgressing the mina’i, "Miniature" and "Kashan" styles, and he is possibly even the driving force behind the whole development of Kashan pottery.

Dates are more common than signatures, and altogether there are some 60 dated vessels between the period 1199 and 1226, which define the heyday of the "Kashan" style. The earliest piece to show the diagnostic scratched-through background is a sherd dated 1199. The next dated vessel comes from 1202 and is signed by Abu Zaid. After 1226 there are no dated vessels for 35 years, until the 1260s when a more simplified form of the "Kashan" style is produced under the Il-Khanids. There are dated tiles from this 35-year period, so we cannot say that the industry died out altogether, however this period of recession may be either a result of the Mongol devastations, or of the simple fact of demise of the leading potters. Again, this will be discussed in section E.

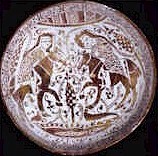

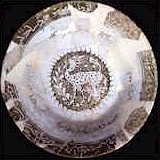

The "Kashan" style sees the development of a new range of vessel shapes (the conical bowl is the most common), new subsidiary motifs and new decorative effects. The most characteristic features amongst the subsidiary motifs are a particular kind of plump arabesque and pigeon-like bird: we can see them on Ashmolean bowl 1956.33, and the large dish in the University of Pennsylvania collection whose decoration consists entirely of combinations of these birds with these palmettes, in a beautiful frieze surrounding a small central figural medallion [Plate 64 in Watson]. Along with these two diagnostic motifs is a large heart-shaped palmette, which occurs especially on the exterior of vessels, and the continuation of the chain-and-stripe motif which we saw on the "Miniature" vessels. The settings are still rather abstract, with landscape indicated by an awning above and a pool below; sometimes plants and trees occur, especially in scenes depicting two horsemen in rendezvous:

|

| [1956.28] |

Click here to study this bowl

The range of subjects is still limited to seated figures, horsemen, princes with attendants, or animals especially gazelles, sometimes dogs, lions, bulls, elephants. There are also many dishes whose decoration is entirely non-figural, and contain arabesques or inscriptions alone.

|

|

|

| [X3126] | [X3128] |

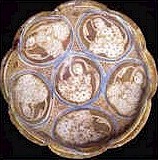

However, a few complex designs are known, and the most famous example is the dish in the Freer Gallery, which was once thought to depict the Persian epic hero, Khusrau, first sighting his beloved Shirin while she bathed. Ettinghausen and Guest in an exhaustive iconographical survey (1961) cast doubt on this reading, and suggest the possibility of a more metaphysical interpretation (mentioned in more detail in D.4 below). This beautiful dish is signed by Shams al-Din al-Hasani, and dated 1210. It was cast from a mould with 29 lobes, and other vessels survive which have been cast from the same mould.

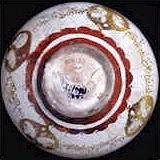

Inscriptions play a more important part in the "Kashan’ style than before, and often occur in concentric bands of different types, surrounding the central decoration. Naskhi inscriptions are both scratched through bands of lustre, and painted on the white glaze, whereas Kufic usually occurs in ornate friezes often against a scrollwork background. The inscriptions are mostly verses, especially Persian quatrains but also some Arabic verses; the subjects are repetitive, and usually mention the cruelty of fate or the ravages of love, and thus have no bearing whatsoever on the subject of the decoration on the vessels. Blessings to the owner are also common, though dedications to particular patrons are not – there are only three known across the whole spectrum of extant Kashan vessels, and none of the individuals has been identified. One of the most elaborate dedications occurs on the Freer dish described above.

|

|

|

||

| [1956.33 base] | [1956.108 base] | [1978.2263] |

Many of these rich and beautiful vessels have a splash of blue or turquoise on them: these seem to be drops of coloured glaze which have fallen from other vessels in the same kiln during the first firing. The splashes were obviously insignificant enough for the potter to continue with the lustrous decoration of his vessel, and may even have been because of the good luck turquoise and cobalt blue were supposed to bring in averting the evil eye. Underglaze blue is sometimes also used by Kashan as an outline to medallions of lustre decoration, and shows another way in which the potters of this period were using their talents and skills to see how far they could go with new techniques.

|

|

|

| [1956.183] | [1978.2258] |

As we have seen above, there are no signed vessels between 1226 and 1261, although there are some dated tiles. When vessel production resumes, the character has changed, the decoration becoming simplified and stylised, the figures stiff with disproportionately large heads, and the potting heavier. New shapes derive from the Chinese vessels that come into the Islamic lands with greater ease under the Mongol unification of two civilisations: the lotus-pod bowl is a popular Il-Khanid type, and often has petals depicted on the outside in imitation of the moulded celadon prototype. For the first time in Islamic art are seen phoenixes, dragons and lotuses, which probably enter the repertoire of ceramic motifs from Chinese silk textiles, rather than ceramics. Thus the tiles at Takht-i Sulaiman show the combination of these motifs with the more traditional Islamic ones.

|

|

|

||

| Views of Takht-i Sulaiman | Tile with phoenix | |||

The peak of Il-Khanid lustre production seems to be the 1270s, and after the 1280s the interest in lustre begins to tail off altogether. The potters become more interested in the potential of underglaze for the types of motifs they now want to paint, that is more freehand designs based on the new Chinese forms. Thus lustre vessels are replaced in popularity by the growth of "Sultanabad" ware. Lustre continues on tiles, however, until the early C14th.

|

| Lustre tile in shrine at Natanz |